Food frequency questionnaires developed and validated in Iran: a systematic review

Article information

Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To systematically review and identify food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) developed for the Iranian population and their validation and reproducibility in order to determine possible research gaps and needs.

METHODS

Studies were selected by searching for relevant keywords in the PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct, Google Scholar, SID, and Iranmedex databases, unpublished data, and theses in November 2016 (updated in September 2019). All English-language and Persian-language papers were included. Duplicates, articles with unrelated content, and articles only containing a protocol were excluded. The FFQs were categorized based on: (1) number of food items in to short (≤80 items) and long (>80 items) and; (2) the aim of the FFQ to explore total consumption pattern/nutrients (general) or to detect specific nutrient(s)/food group(s) (specialized).

RESULTS

Sixteen reasonably validated questionnaires were identified. However, only 13 presented a reproducibility assessment. Ten FFQs were categorized as general (7 long, 3 short) and 6 as specialized (3 long, 3 short). The correlation coefficients for nutrient intake between dietary records or recalls and FFQs were 0.07-0.82 for long (general: 0.07-0.82 and specialized: 0.26-0.67) and 0.20-0.67 for short (general: 0.24-0.54 and specialized: 0.20-0.42) FFQs. Long FFQs showed higher validity and reproducibility than short FFQs. Reproducibility of FFQs was acceptable (0.32-0.89). The strongest correlations were reported by studies with shorter intervals between FFQs.

CONCLUSIONS

FFQs designed for the Iranian population appear to be appropriate tools for dietary assessment. Despite their acceptable reproducibility, their validity for assessing specific nutrients and their applicability for populations other than those they were developed for may be questionable.

INTRODUCTION

Diet is a major lifestyle-related risk factor for chronic disease. Therefore, methods of assessing dietary intake in epidemiological studies need to be evaluated. Food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) are the most commonly used tools to estimate usual dietary intake, especially in large epidemiological studies of nutrition [1,2]. FFQs are considered a “screener” method, developed to evaluate and rank the intake of nutrients or food groups to investigate associations between diet and disease [3].

FFQs are popular because they are less expensive, easier to use, and less time-consuming than other methods, and have the ability to capture long-term dietary intake [4]. However, despite their considerable advantages, FFQs may not be well-structured and appropriately used [5]. Factors such as respondents’ characteristics, the quantification of food intake (by portion size), and quality control and management of data may influence the accuracy of dietary intake assessment [6]. To categorize individuals accurately according to their nutrient intake, the validity and reproducibility of any FFQ should be assessed [7].

FFQs consist of a list of selected food items for which the respondent is asked to indicate how often they eat each item per day, week, or month. The list of foods may be chosen for the specific purposes of a study, and therefore may not assess respondents’ total diet. Furthermore, the food list may vary based on the ethnic, social, and cultural background of the population, and should be tailored to reflect those characteristics [2]. Therefore, the usefulness of FFQs depends on the appropriateness of the food list, which should reflect the usual food items or dishes consumed by the studied population. Furthermore, the specific accuracy of FFQs can be less than that of quantitative dietary assessment methods [8]. Accurate data on the amount of food and beverage consumption depends on assumptions for standardized portion sizes compatible with the amounts commonly consumed per serving in a culture or age/gender group [2,8]. Therefore, FFQs need to be adapted and validated for use in different specific contexts.

In Iran, the use of FFQs is relatively recent, dating from the early 2000s [9]. No comprehensive review has been conducted on FFQs developed and validated in Iran. Therefore, the present study aimed to systematically review FFQs developed and validated in Iran in order to identify possible research gaps and needs in this regard.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A systematic review was carried out by searching with relevant keywords or phrases, including “food frequency questionnaire,” “FFQ,” “reliability,” “validity,” and “Iran,” in the Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, ProQuest, PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, Science Direct, SID, and Magiran (in Persian) databases, unpublished data, and thesis websites such as Irandoc (in Persian). Unpublished articles were obtained by contacting the authors to compare the food or nutrient items, as well as the questionnaire structure. The inclusion criteria were original human studies on FFQ validation performed on Iranian subjects published in the English or Persian languages. The reference lists of selected articles were checked to find additional related articles. If the full text was not provided for an abstract, the authors were contacted.

Initially, 29 articles were found. Two reviewers who were experts in the subject matter then analyzed the titles and abstracts of the selected articles to confirm their inclusion. Duplication was also checked and 19 articles remained. In the next step, one study [10] was excluded as it did not contain a full report and 2 unrelated articles (based on content) were also excluded (Figure 1). Finally, 16 papers met the criteria for the systematic review, based on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist. The methodology for this systematic review was registered in the International Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews (in process; receipt code: 154722).

For each study, the following data were extracted: FFQ type, method of development, number of food items in the food list, questions on portion sizes, number of response categories for intake frequency, dietary reference method, and time interval between applications of the FFQ (for reproducibility), whether deattenuation and/or adjustment for energy was done, and number of nutrients evaluated. Data were categorized based on nutrients and food groups.

The questionnaires were categorized into general FFQs and specialized FFQs that were developed for assessing special nutrients or food groups. Furthermore, based on the number of food items in the food list, FFQs were classified as short (≤ 80 items) or long (> 80 items). This cut-off was based on a previous study [11] and arbitrary agreement between the authors. Validity (based on extracting the correlation coefficients between diet records (DRds)/recalls and FFQ estimates or agreement/disagreement between categories of mean/median/frequency of nutrient/food group consumption [cross classifications] between the FFQ and the reference method) and reproducibility (correlations between repeated administrations of the FFQ) were assessed. The values used to categorize the strength of correlations were based on a similar study by Wakai [12], which used the following criteria to categorize the strength of correlations: correlation coefficients 0.60 or more were considered high correlations, while correlation coefficients of 0.40-0.59, 0.30-0.39, < 0.30 were considered to indicate moderate, fair, and poor agreement, respectively. These cut-offs were used to define the validity of FFQs.

Ethics statement

As the present study was a systematic review, no ethics statement was needed.

RESULTS

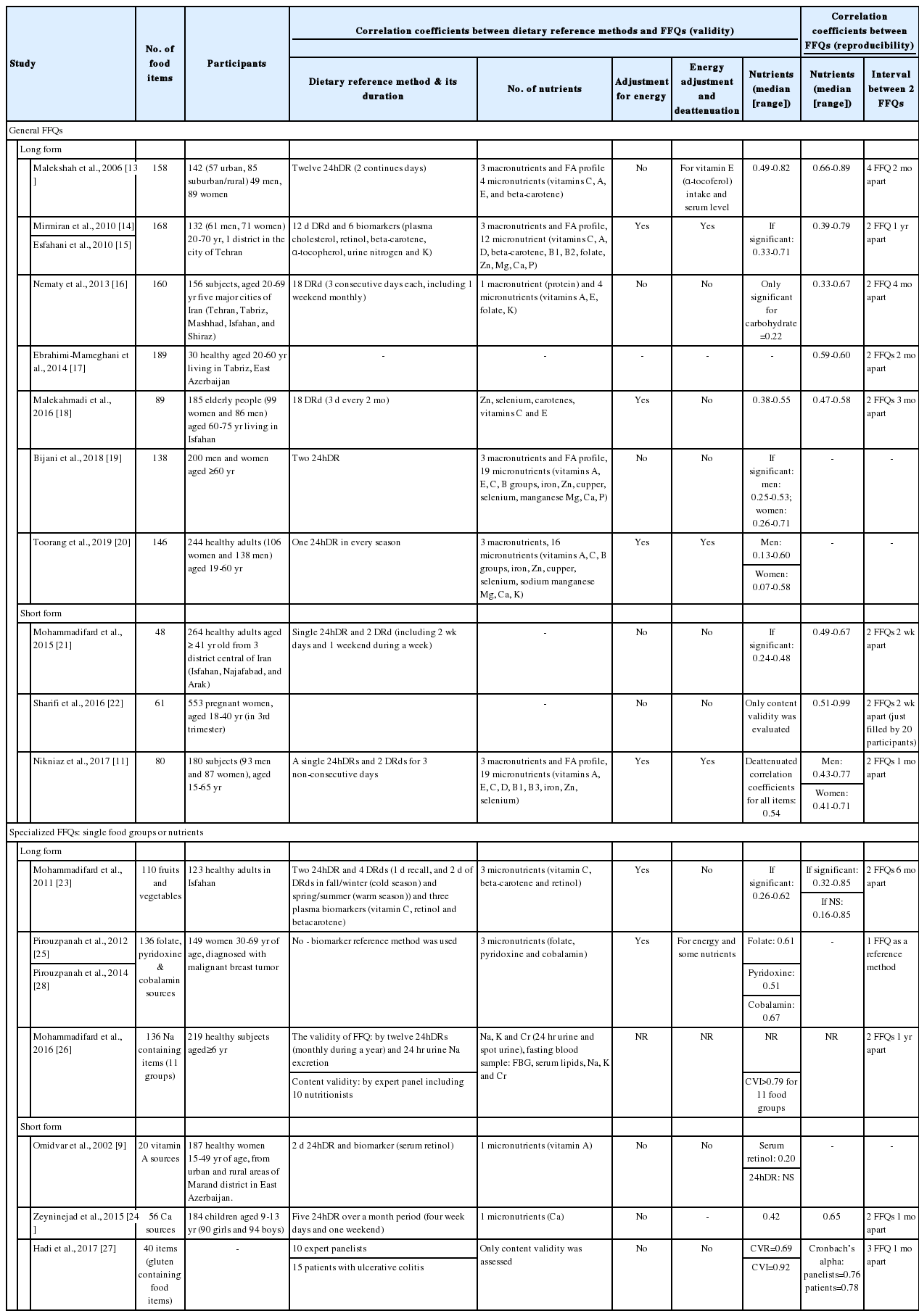

Based on the literature search, 16 FFQs met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). They were all published, although in some cases missing information in the articles was identified through contacting the authors. No FFQ was found by searching unpublished data.

Characteristics of food frequency questionnaires developed and validated in Iran

The detailed characteristics of FFQs, including the food list, presence of questions on portion/serving sizes, method of development, and type of questionnaire, are presented in Table 1. Most FFQs (n= 14) [13-26] were semi-quantitative, 2 were qualitative [9,27] and only one was considered quantitative [20].

Ten of the FFQs were general questionnaires that included food items from all food groups [11,13-21], of which 7 had a long format (89-189 food items in the list) and 3 were short (48-80 food items). They were all validated for adults, except for 2 that were specially designed and validated for elderly individuals [17,18].

The other 6 FFQs were categorized as specialized FFQs, which had been developed to estimate the intake of specific nutrients (vitamin A, calcium, folate, pyridoxine and cobalamin, and sodium) or food groups (fruit and vegetables). Among the specialized FFQs, 4 had a long format [23,25,26,28], while the other 3 were short [9,24,27]. All the specialized FFQs were developed for adults, except for an FFQ on calcium, which was developed for school-age children [24], and an FFQ on sodium sources, which was developed for those aged 6 years and above [26].

The approach used to develop the food list in 7 FFQs was databased [9,11,14,15,22,23,26], in which food items for the FFQ food list were chosen according to data from DRds or recalls. Only one FFQ [27] used an experience-based method by selecting food items based on the opinions of an expert panel regarding the most common food items or foods usually consumed in the study population. Three were developed through a combination of databased and experience-based approaches [13,18,24]. In addition, 2 questionnaires were modified versions of the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS) FFQ, in which new food items were added using an experience-based approach [17,19], and 3 questionnaires were translated and modified versions of original questionnaires from other countries [20,25,28].

Comparison of food items in Iranian food frequency questionnaires

Long-format questionnaires, except for the dish-based FFQs [16,20], included food items based on food groups. Common food items in Iranian FFQs included 9 items for breads and cereals (4 main traditional types of bread, rice, spaghetti, noodles, biscuits, and crackers); 4 dairy products without considering the fat content and processing type (milk, yogurt, cheese and doogh/yogurt drink); 17 fruits (bananas, oranges, apples, pears, plums, peaches, apricots, nectarines, cherries, melons, watermelon, grapes, pomegranates, canned fruit, dates, dried fruits, and fruit juice); 16 vegetables (dark green vegetables, lettuce, tomato, cucumber, eggplant, squash, onion, garlic, carrot, bell pepper, green pepper, corn, potato, cabbage, green beans, and green peas), meat, poultry, fish, and eggs (each as a single item); 6 legumes (lentils, chickpeas, split peas, dried beans, soybeans, and broad beans); 5 nuts (pistachios, almonds, peanuts, hazelnuts, and walnuts), 2 seeds (sunflower and pumpkin); 4 items for oils and fats (hydrogenated vegetable oil, vegetable oil, olive oil, and butter); and 1 sweet (chocolate). Pizza, although it is considered a dish, was included in 2 food items–based FFQs [14,15,17]. In addition, although the common items listed above were based on dietary pattern(s) of the population under study, other items were added to the FFQs’ food lists, such as traditional dairy foods, such as camel doogh and aqaran, smoked and salted fish, as well as yellow oil in the FFQ developed for the Golestan cohort study [13].

Of the developed and validated questionnaires, one was dishbased [16], and another included a combination of common general food items and common dishes consumed by Iranians [20].

Validity and reproducibility of food frequency questionnaires in Iran

In most studies, the validity of the developed FFQ was evaluated by assessing the correlation of dietary intake estimates against 24-hour dietary recalls (24hDRs) [9,11,12,18,19,22,23], DRds [14,15,17], or nutrient biomarkers [9,13,20,22,24,27] as reference methods (Table 2). The correlation coefficients between measured nutrients from FFQs and reference measures were between 0.07 to 0.82 in the general FFQs and 0.20 to 0.67 in the specialized FFQs. All proposed questionnaires appeared valid, except for one [14]. Six studies reported high correlations (r≥ 0.60) between FFQ estimates and reference measure(s) [13-15,20,23,25], 11 presented moderate correlations (r = 0.40-0.59) [11,13-15,18-21,23-25], 9 had fair correlations (r=0.30-0.39) [14,15,18-21,23-25], and 6 had poor correlations (r< 0.3) [9,16,19-21,23] for some food groups/nutrients derived from FFQs.

The range of correlation coefficients for short FFQs (r= 0.20-0.54; general: 0.24-0.54; specialized: 0.20-0.42) was slightly lower and narrower than that of long FFQs (r= 0.07-0.82; general: 0.07-0.82; specialized: 0.26-0.67).

Some studies demonstrated benefits from assessing additional validity method(s) such as cross-classification to discover the ability of the developed FFQ to accurately classify subjects by groups of intake (data not shown) [11,14,15,19-21,23,24]. Statistically, complete agreement was reached when subjects were in the same intake category according to 2 methods; adjacent agreement was when participants were categorized into roughly similar groups (e.g., the second quartile of intake by FFQ but the third quartile of intake by the reference method); and complete disagreement was observed if subjects were classified into the lowest intake class by FFQ and highest intake class by the reference method or vice versa. Complete agreement observed between food/nutrient items from 20% to 91% while disagreements was reported sparingly, ranging from 0% to 19%. A subanalysis by gender revealed that the mean agreement was higher in men (31.0-68.3%) than in women (27.0-54.1%), and the frequency of complete disagreement was similar in both (men: 0-21%; women: 0-25%). In most items, complete and adjacent agreement was observed and disagreement was seen mostly in food that were consumed seldomly (e.g., pickles) and some micronutrients (vitamins D, B12, B3, beta-carotene, calcium, and iron).

One study only tested agreement by Bland–Altman scatter plots [19], and found that almost all individuals showed consistent variations across levels of intake, and only a few participants fell outside the limits of agreement for energy and macronutrients.

Reproducibility of all but 4 questionnaires had been assessed [19,20,29,30]. To evaluate reproducibility, the FFQs were completed twice within an interval of 2 weeks [21,22] to 1 year [14,15]. In one study [13], 4 FFQs were completed at a 2-month interval. All studies had acceptable reproducibility, with significant correlations between nutrient intake values (ranging from 0.32 to 0.89). The strongest correlations were reported by studies with shorter intervals between the 2 FFQs [13,21,22].

DISCUSSION

Sixteen FFQs (10 long and 6 short) that were developed and validated for the Iranian population were identified. Most of the questionnaires were reasonably valid and reproducible (16 valid and 13 reproducible). However, relatively poor validity was observed in FFQ estimates for several food groups and nutrients. FFQs with a long format had slightly better estimations of nutrient intake. Almost all FFQs used for dietary assessment in the Iranian population were developed and validated for adults, except for one developed to assess calcium intake in children [24] and 2 developed to assess dietary intake in the elderly [18,19].

The Iranian FFQs were mostly validated against a dietary reference method (24hDRs [9,11,13,19-21,23,24,26] or DRds [11,14,15,16,18,21,23]) and, in some cases, biomarkers [9,14,21,23,25,28]. The range of correlations for nutrient intake estimates between the dietary reference method and Iranian FFQs were similar to those reported for Japanese FFQs (0.42 to 0.52) [12], but lower than that reported for Western countries (0.60 to 0.74) [29]. A systematic review of FFQs developed and validated for the Brazilian population showed that the correlations reported between FFQs and the reference method were equal to or less than 0.4 for certain nutrients and above 0.4 for others [30]. As Wakai [12] stated, “This variation may be due to differences in the number of food items, ability to recall intake frequencies and portion sizes, the wording of questions in the FFQ, and between-person variations in consumption among food groups.” For example, in short FFQs, smaller numbers of food items in the food list may lead to weaker correlations between dietary recalls and FFQs.

None of the reviewed studies reported the response rates of FFQs. Thompson & Subar [2] noted that although longer FFQs can better reflect the total diet, short FFQs can have higher response rates and are less burdensome for respondents. Additionally, the inclusion of mixed dishes and traditional foods in some Iranian FFQs may have led to higher variation, even in long FFQs, while list-based questionnaires could not reflect information on the items used by various subcultures, including detailed information on food preparation, cooking methods, and additives [3].

Among all the Iranian validation studies that were reviewed, only three explored correlations between estimations of food group intake based on a reference method (DRd or 24hDR) and those made based on FFQs [23]. Mohammadifard et al. [21] also investigated the effects of season on these correlations and found considerable correlations between dietary recalls and FFQs for total fruit/vegetable intake in both hot and cold seasons (0.60 to 0.62). According to Wakai [12], variation in food group correlations between the reference method and the FFQ depends on the definition of portion size and the number of food items listed in the FFQ. Food items with an easier and more understandable portion size (for example 1 medium raw carrot in comparison with 1/2 cup of cooked vegetables) result in higher validity.

Questionnaires designed to assess the intake of a single nutrient had different degrees of validity, depending on the type of nutrient studied. One FFQ that was specifically developed to assess folate, pyridoxine, and cobalamin intake had acceptable validity, with correlations between DRds and FFQ ranging from 0.51 to 0.67 [25]. Additionally, the validity of a questionnaire designed specifically for calcium intake in children was close to the acceptable range (r= 0.42) [24]. Similar to the Iranian FFQ for calcium [24], a systematic review of FFQs developed for calcium intake in children found good validity in children 12 months to 36 months of age, and concluded that semi-quantitative FFQs were valid and reproducible for assessing dietary intake at the group level [32]. In addition, the findings of a systematic review on dietary assessment methods in children 11 years of age or younger suggested that FFQs can be more reliable and valid than other dietary assessment methods (i.e., 24hDRs and DRds) in this age group [32]. However, another review of FFQs developed for children and adolescents concluded that FFQs were the most valuable method for assessing total energy intake in children aged 4 years to 11 years, compared to total energy expenditure measured by double-labeled water. In contrast, for younger children aged 6 months to 4 years, weighed DRds provided the best estimate, whereas diet history provided better estimates for adolescents aged ≥ 16 years [33].

Furthermore, for some nutrients, respondents’ gender was associated with the strength of the correlations; for example, the correlations for beta-carotene, vitamins A, and C were lower for women than men in the TLGS [14,15]. This finding is remarkable given the presumption that women usually report intake more accurately than men, due the fact that they are usually responsible for food preparation and can provide more accurate response(s) [34]. In contrast, one study reported considerably weaker correlations for energy, fat, and micronutrients in men than in women (0.07-0.19 vs. 0.76-0.81) [16].

This review reported all available FFQs validated in the Iranian population, which may also be useful for populations in other Middle Eastern countries; however, it faced with some limitations that should be considered. The results of various studies were not completely comparable due to differences in the micronutrients or macronutrients studied for validation. Additionally, the FFQs differed in terms of the number of food items included and the purpose of their development (measuring specific nutrients, populations, or diseases), which may influence their interpretation.

CONCLUSION

The FFQs designed for the Iranian population appear to be appropriate tools for dietary assessment; however, their validity for assessing specific nutrients and their applicability for populations other than those they were developed for may be questionable. Nonetheless, there was a large amount of commonality among the general FFQs. Therefore, choosing the proper FFQ for a specific population within Iran should be done with caution, and an analysis of their characteristics may be necessary. The lack of a general FFQ that can be used at the national level in Iran while being adjusted according to the dietary patterns of different ethnic and cultural groups is a gap that needs to be filled by future studies. Furthermore, the fact that few FFQs were developed for elderly individuals and children makes it difficult to judge their generalizability and usefulness for those age groups.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare for this study.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, NO. Data curation: NO, AR, KLT. Funding acquisition: None. Methodology: NO, AR. Project administration: NO. Visualization: NO, AR. Writing – original draft: NO, AR. Writing – review & editing: KLT.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Ahmad Esmailzadeh for his constructive comments and suggestions.